New York Review of Architecture, reconocida revista de arquitectura de Estados Unidos, publicó en su último número de mayo-junio una extensa entrevista a los académicos Hugo Palmarola, Eden Medina y Pedro Alonso. La entrevista trata sobre las implicancias de su libro “How to Design a Revolution. The Chilean Road to Design”. El número 40 de la revista fue lanzado el 4 de mayo en Nueva York en un evento al que asistieron 300 personas.

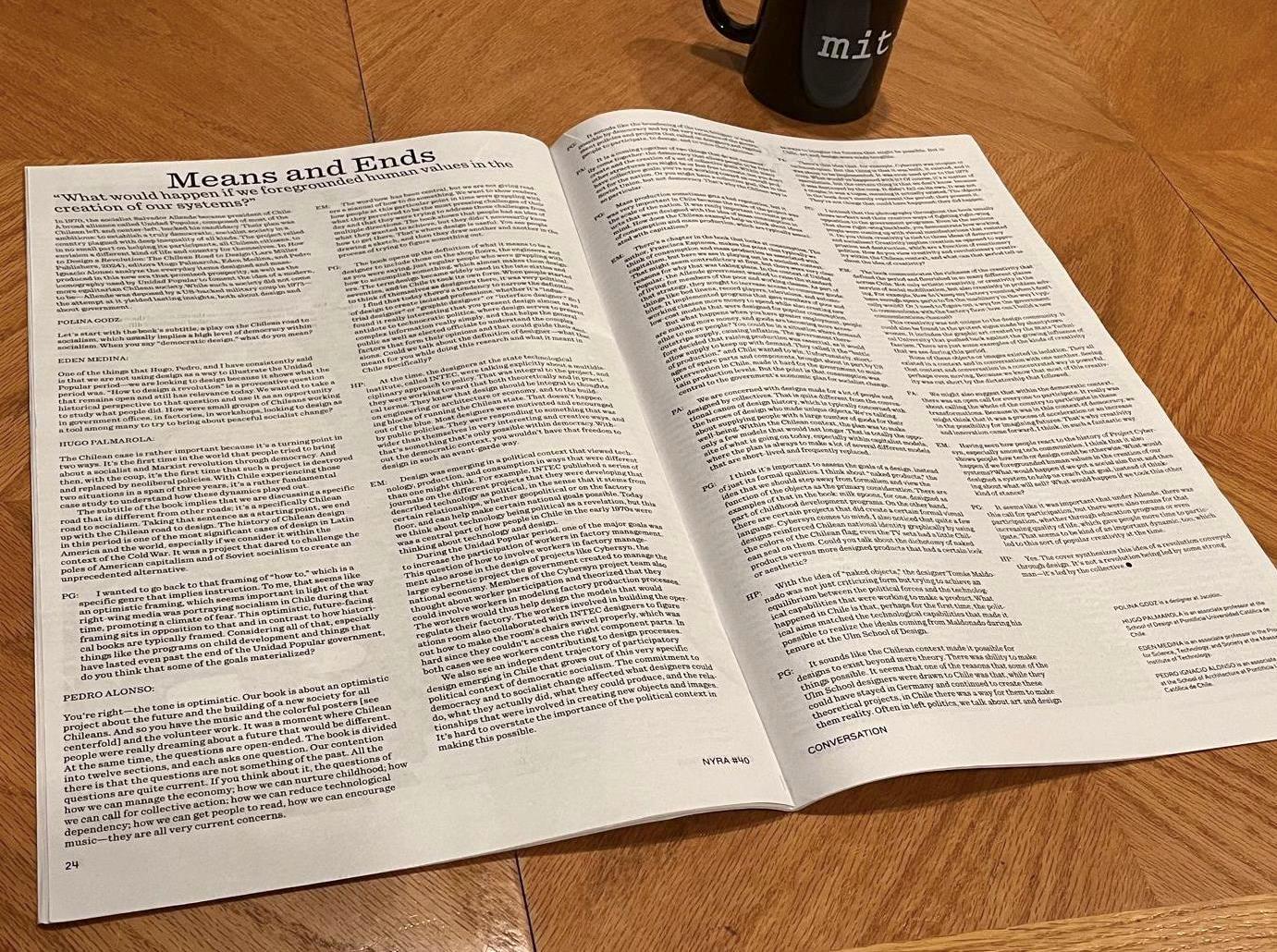

La entrevista titulada “Means and Ends” fue realizada por Polina Godz, investigadora y diseñadora de Jacobin Magazine. New York Review of Architecture publicó adicionalmente a doble página uno de los carteles más destacados de la oficina de diseño de los hermanos Larrea, cartel dedicado a la protección de la infancia que también forma parte del libro.

El libro de Palmarola, Medina y Alonso había sido presentado recientemente en Estados Unidos, durante marzo en la Universidad de Columbia en Nueva York, dentro de The University Seminar on Latin America perteneciente a The Institute of Latin American Studies, así como en MIT en Cambridge Massachusetts, dentro de MIT Morningside Academy for Design. Instancias académicas de postgrado dedicadas al trabajo interdisciplinario donde el libro fue considerado una contribución a la comprensión de un período histórico fundamental.

“How to Design a Revolution” es un libro de distribución global publicado por Lars Müller Publishers (Zurich, 2024). Se trata del primer libro de análisis integral sobre el diseño industrial y gráfico durante el gobierno del presidente Salvador Allende, considerado uno de los casos más significativos de diseño en Latinoamérica y el mundo.

Extractos de la entrevista en New York Review of Architecture:

Eden Medina:

“One of the things that Hugo, Pedro, and I have consistently said is that we are not using design as a way to illustrate the Unidad Popular period—we are looking to design because it shows what the period was. “How to design a revolution” is a provocative question that remains open and still has relevance today. We wanted to take a historical perspective to that question and use it as an opportunity to study what people did. How were small groups of Chileans working in government offices, in factories, in workshops, looking to design as a tool among many to try to bring about peaceful socialist change?”

“Most designers were motivated and encouraged by public policies. They were responding to something that was wider than themselves in very interesting and creative ways, and that’s something that’s only possible within democracy. Without the democratic context, you wouldn’t have that freedom to design in such an avant-garde way”.

Hugo Palmarola:

“The Chilean case is rather important because it’s a turning point in two ways. It’s the first time in the world that people tried to bring about a socialist and Marxist revolution through democracy. And then, with the coup, it’s the first time that such a project is destroyed and replaced by neoliberal policies. With Chile experiencing those two situations in a span of three years, it’s a rather fundamental case study to understand how these dynamics played out”.

“The subtitle of the book implies that we are discussing a specific road that is different from other roads; it’s a specifically Chilean road to socialism. Taking that sentence as a starting point, we end up with the Chilean road to design. The history of Chilean design in this period is one of the most significant cases of design in Latin America and the world, especially if we consider it within the context of the Cold War. It was a project that dared to challenge the poles of American capitalism and of Soviet socialism to create an unprecedented alternative”.

Pedro Alonso:

“We are concerned with designs made for a lot of people and designed by collectives. That is quite different from the conventional canon of design history, which is typically concerned with the heroes of design who made unique objects. We’re talking about supplying people with a large number of goods for their well-being. Within the Chilean context, the plan was to make only a few models that would last longer. That is totally the opposite of what is going on today, especially within capitalist models, where the plan is always to make a lot of several different models that are short-lived and frequently replaced”.

“There’s this idea that, for example, Cybersyn was utopian or technoutopian. But the thing is that it was built, it existed, and it was about to be implemented. It was even used prior to the 1973 coup. What would’ve happened with it? Of course, it’s a matter of speculation, but the certain thing is that we don’t know, because it was destroyed by the coup. It didn’t fail on its own. It was not a utopia; it was a topos, meaning it actually existed. The objects in the book don’t merely represent the period; they present it. They’re not things that could have happened; they did happen”.

Polina Godz:

“It sounds like the Chilean context made it possible for designs to exist beyond mere theory. There was ability to make things possible. It seems that one of the reasons that some of the Ulm School designers were drawn to Chile was that, while they could have stayed in Germany and continued to create these theoretical projects, in Chile there was a way for them to make them reality. Often in left politics, we talk about art and design as ways to imagine the futures that might be possible. But in Chile, art and design were made tangible”.